Los Angeles, at first glance, is a desert both actual and metaphorical. The wide-open spaces between destinations mean culture is spread as thin as butter on a model’s weekly piece of toast. In spite of these inhospitable conditions, museums abound in the municipality, like weeds pushing their way through cracks in concrete. Oases with art, and air conditioning.

Last Friday, the baby, my friend James, and I headed to The Getty. Perched on the top of one of the Santa Monica Mountains, the museum is a prime example of what billionaires can do for YOU. I’d say it’s the Met of Los Angeles, if the Met looked like the building where the government convenes in a post-apocalyptic space society. And if the Met was less art, more vibes.

After you park, you walk upstairs to a tiny, pristine garden. Everything is neutral and neat—like Gwyneth Paltrow. A tiny tram arrives to ferry you up the hill, tinkling out instrumental piano from invisible speakers. The journey terminates in a plaza forged of the same yellowish travertine as the buildings that rise from its perimeters. Buckets of parasols, the same beige as their surroundings, are discreetly placed at entrances and exits of buildings, passively offering their services to passersby as a shield from the unremitting sun.

Our first order of business was lunch. The setting suggested champagne and oysters, but we ended up with the requisite institutional cardboard. We gnawed through it, our mastication mostly drowned out by the fountain gently bubbling nearby. Moderately fueled, we proceeded to experience the art.

At my ripe age, I find art museums overwhelming. It’s hard to appreciate the beauty of a masterwork when its being viewed in concert with hundreds of other masterworks. It depresses me to think about a gifted painter, finishing the best piece they’ll ever work on in their entire lives, and then years after their death that painting just being one of a whole bunch that people are skipping past to get to the Mona Lisa or whatever. At the Getty, there was a Dutch painting by a student of Rembrandt where the light was so perfectly captured it made me gasp. I can’t remember the name of the artist. I guess the lesson is something about ego and life being ephemeral but it can’t help make me think about my own pathetic striving and how soon it will all be forgotten.

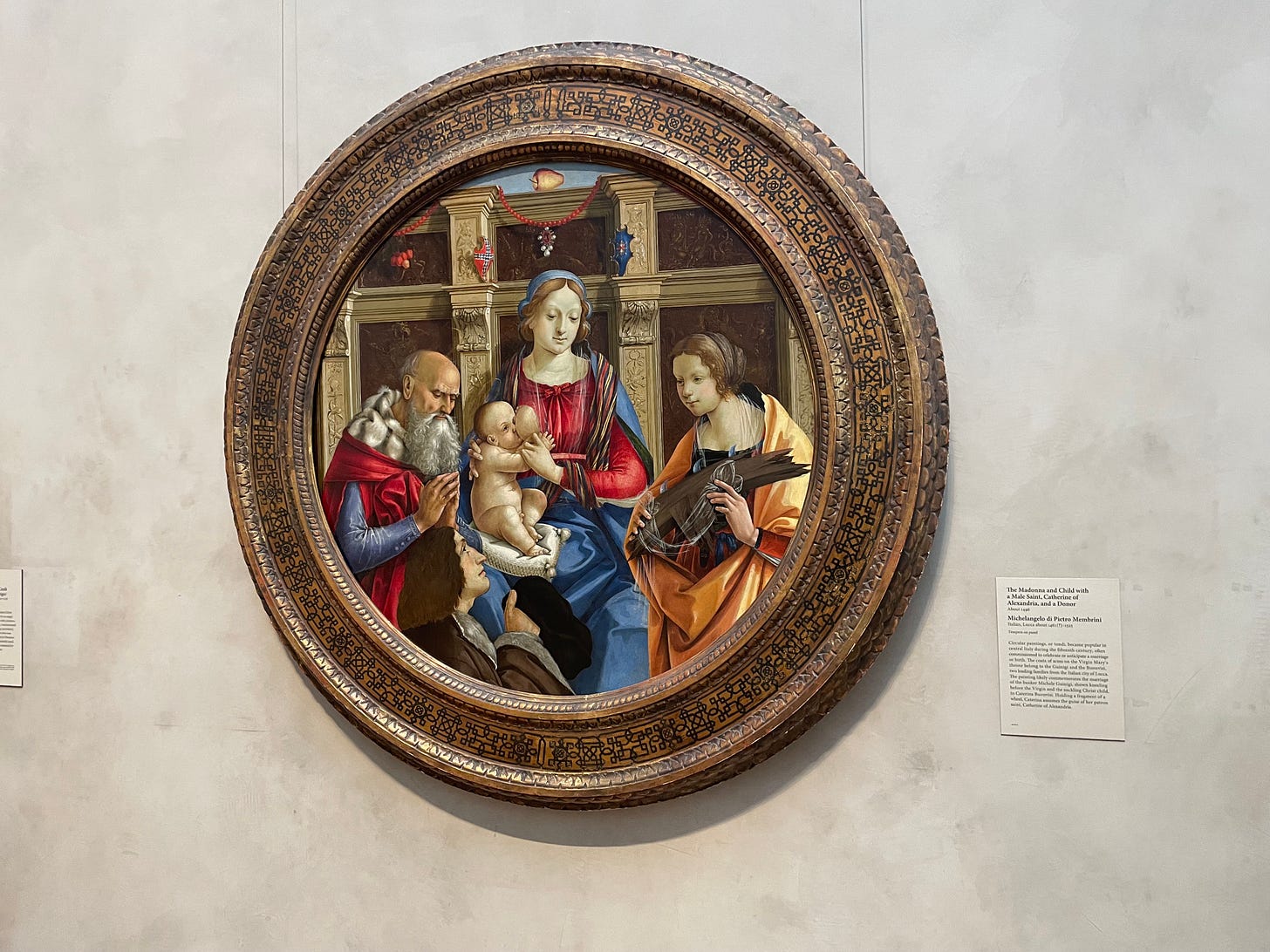

On the other hand, museums are good for finding paintings of weird looking people and telling the person you’re with the subject looks like them, which is what James and I did for most of the afternoon. As a breastfeeding mother, I felt over-represented in Renaissance portraiture.

After we did our requisite gallery browse, we headed out to my favorite part of the Getty: the garden. An Alice in Wonderland-esque labyrinth of flowers encircled a pond filled with boxwood hedges. Navigating the narrow gravel paths with a stroller was a new challenge, but butterflies still flitted, maintaining the sense of tranquil idyll.

In the Getty garden, you can pretend you’re an aristocrat, surveying the lands temporarily granted to you by generational oil wealth. We sniffed the roses as if we had grown them ourselves—or, more accurately, commanded our gardener to grow them for us.

As we circled the path, I sighted a celebrity: Karla T., of the “Stuck at Prom” competition. A local teen, she was a finalist in Duct Tape’s annual scholarship granted to the person who makes their prom attire from…you guessed it…Duct Tape. A few weeks earlier I had read about the hours she and her mom spent making her Marie Antoinette-inspired dress in the LA Times.

She was there for a photo shoot, trailed by an entourage of museum employees. But for the occasional glint of sun off her dress, you wouldn’t have known it was duct tape. Like the velvet robe in an oil painting, it would forever be an imitation of the genuine article (of clothing) and that’s something nice about art—looking at life from a slight, overwhelming distance.

And the same can be said for my city (despite my protestations, LA is my city) viewed from that peak of the Santa Monica mountains as we wound our way back down on the tram. Something a little gentler, a little more manageable, a little more digestible than what we’d see on our long rush hour drive home.